This story by Sarah Miller is published at The Cut: The Best Abortion Ever: In my rural California county, it used to be impossible to get an abortion. When I was 41, I needed to have two.

In the rural California county where I live, there’s a decent chance of a tree falling over onto my house (this has happened to several friends), an even better one of contracting the measles (we have one of the lowest vaccination rates in the country), and, until very recently, a zero percent chance of getting an abortion.

The year I was 41, I needed two of them. I was no stranger to abortions; I’d had two before, but never in the same year. In fact, 30 percent of the times I had sex in 2011, I got pregnant. So there I was in November, having already aborted 50 percent of that year’s pregnancies, hoping to make it a nice round 100 percent. I just had to decide how.

In January, I had decided to terminate with RU-486, the abortion pill. I got in my car, drove up to Chico to get my prescription, and came home. I didn’t stress about it. I figured I’d get some spaghetti and some maxi pads and stay home for a night, watch a season of something, texting people, “I’m having a friggin’ abortion, ikr, argh,” and I’d wake up not pregnant. While I’m happy that medical science has come up with a way for women to end unwanted pregnancies in the comfort of their own homes, my experience with RU-486 wasn’t anything like the fantasy described above.

First, it is not the abortion pill; it’s the abortion pills. There are three of them. Pill No. 1 dislodges the embryo, pill No. 2 encourages it to make haste out of your uterus, and pill No. 3 makes sure you don’t vomit up No. 2. The night I took them, I covered all the bases of physical misery: I bled. I was nauseous. I had cramps. I could not get comfortable. I couldn’t read. I couldn’t watch TV. I could only thrash around and fail to imagine ever feeling better. (Thank God for marijuana, which was helpful.) I decided right there that I’d prefer carrying a baby to term, raising him up from infancy all the way to the proud moment where I’d give him a nail-studded club with which to stave off the fascists fighting to take control of our family water supply, than go another round with RU-486, which is basically ayahuasca minus the spirit animals. For my fourth abortion of my adult life, I knew I was going to have to go with the old classic.

I was already familiar with surgical abortions, also sometimes called vacuum aspirations, where suction is used to remove the fetal tissue. I’d had two of them, when I was younger, both of which sucked for different reasons, but, in their defense, did result in my not giving birth.

My first was in New York in the early ’90s, when I was 24, at a clinic. It took a whole day, during which I was herded around to a series of freezing rooms with a fairly large group of women — maybe 15 of us — in these absurdly short robes they’d given us to wear. When sitting or walking, I had to hold mine down with two hands. “Yes, Miss, please, how do we get this thing to cover our hoo-has?” one of the women in my group shouted out to one of our handlers. We were made to watch a film explaining what an abortion was — just in case I had mistakenly stumbled into Jimmy’s Leg Removal Emporium. As they put me under — abortions accompanied by general anesthesia are called “twilight” — I was still giggling about the hoo-ha joke.

I fell asleep in ’90s New York and woke up in what appeared to be Victorian England, in a high-ceilinged damp room crowded with stretchers and decorated with curlicues of peeling paint in the appropriate shade of aqua seafoam shame. I was clutching my abdomen in pain, and so was everyone around me. The hoo-ha lady vomited into her hands. Again, there were maybe 15 women in that room, wanting help from maybe four nurses, all of whom seemed to not want to be there, all of whose expressions seemed to say: “You should have thought of this before you let someone come inside you, you whore.”

My second abortion was better and therefore I remember it less. It was in Philadelphia. I had real insurance and there was an element of privacy at the hospital; nevertheless, afterward I felt like shit and bled and bled and bled, for days.

***

I have a precise memory of asking my mother what an abortion was. I was around 10. “It’s when you were going to be pregnant,” she said, “but they make it so you’re not.” I believed everything about this. On the day when I found out that I was pregnant for the second time in 2011, I wanted so much to snap my fingers and magically make the whole thing go away. I wanted abortion to be what my mother said it was, and even though I knew abortion was what she said it was, the actual experience had really never reflected that truth.

As I waited for my diagnostic appointment — it was probably a week before they could get me in, a long week — I started to wonder if I could actually do it again. I didn’t want to endure the days of being pregnant and watching my breasts swell. And I didn’t want to drive to Chico to get the abortion and drive back afterward, in pain, bleeding, pulling over in dusty farm towns to change maxi pads. I thought about a friend of mine who grew up in my county who had told me she’d had her son here 20 years ago because she didn’t have $350, or a car.

I didn’t want to feel that pain. I didn’t want to bleed the blood. Most of all, I didn’t want to spend the time waiting. While you wait, you just have to walk around being pregnant when you know you don’t want to be a mom, and meanwhile you kind of are a mom, and you never notice how much our culture is about moms and motherhood until you’re at a point in your life when you really, really do not want to think about it.

But I also didn’t want to have a baby. So I got in the car and got out in front of the clinic, and was confronted with something that shouldn’t have been surprising, but was anyway: protesters. There were two of them, both stern, doughy pale men, one young, one old. A clinic escort met me at my car. “Don’t look; don’t look,” she kept saying. “Don’t say anything to them; don’t look.”

I looked. I couldn’t help it. Their big signs showed blood and viscera, but I didn’t linger on the images; I could just as well have been looking at a human heart as a fetus. Neither the men or their signs made me feel any worse than I already did.

The clinic was dark and utilitarian and comforting. While I was filling out an intake form, I started to cry. I was over 40. I was underemployed. As I wrote my partner’s phone number on the “in case of emergency” part of the form I thought about how I really honestly should just put my parents or my brother, because if they called my partner he’d be like, “Ugh, Jesus, what a pain.” In that moment I knew that my relationship was over. Maybe I should just have a baby, the thought came again, stronger than ever. Maybe it could be my last chance of having someone love me. And also, just as a very immediate perk, I would leave this place right now.

I put down my pen and thought about what it would be like to just have a baby instead of getting an abortion.

The receptionist called my name again.

“I’m almost done,” I said. But she beckoned. She looked like she had a secret.

“I see you’ve opted for a twilight today,” she said, referring to my chart. “And it’s totally fine if you want to be put under, we support that.”

I told her the last surgical abortions I’d had, granted a long time ago, had really sucked, and I would just as soon not be awake. “And being awake for RU-486 sucked, too,” I said, hurriedly adding that this wasn’t her fault and I was fully in support of the drug, etc.

She nodded. She said RU-486 could be “intense.” Then she explained that for early terminations, they now used handheld manual aspirators, rather than vacuum aspirators, that made the process faster and less invasive. “We’ve gotten wayyyyyy better at abortions,” she said. “And if you don’t go under, the recovery time is a lot less. And what I really wanted to let you know is this …” She lowered her voice to a conspiratorial whisper. “The woman who works on Tuesdays is amazing.”

“I don’t know,” I said. “Doesn’t it hurt?”

“It hurts for like a second,” she said. I liked her manner. I pictured her in class, raising her hand when she knew the answer. “It hurts for a few seconds, but then, I swear to God, it’s over. And then it’s just fine.”

“Okay,” I said, “I’ll do it.”

She looked so happy. She actually said yay, as she tapped my file on the counter. “This woman is seriously just so incredible at abortions,” she said. “I think you’re really going to like it.”

This was kind of a weird thing to say, but I was into it.

The clinic gave me a companion to guide me through the procedure. She was in her late 20s, soothing, somber, hippie-adjacent. She wouldn’t laugh at my jokes. “Just keep squeezing my hand” was all she said. “Just look at me and keep squeezing my hand.”

***

The abortion room was tiny and plain and clean, like a studio-apartment kitchen. I squeezed my companion’s hand through the speculum portion of things, which is fine for me, but in this context, a little more traumatic than your average Pap smear speculum, then through the Novocain shot, which was actually more pleasant than a Novocain shot you get in your mouth. “We wait a few moments,” the doctor said, in an Eastern European accent.

In a minute or so, she said, “Okay, now instrument.” There was a feeling between uncanny and mildly unpleasant, then there was pain. It was like the worst cramp ever times three, but not worse than that. “Just look at me and keep squeezing my hand; just look at me and keep squeezing my hand,” said my companion, and I did what she said, and was finally glad that she’d invested more of her personality in solidity than in wit. It lasted about ten seconds. I was just about to say, “This really hurts,” when, suddenly, it didn’t hurt anymore, and the doctor was snapping off her gloves.

“Was that it?” I said as I felt the speculum come out. The doctor didn’t say anything, but my companion said, “That’s it. You did great.”

“Holy shit,” I said. “That was hands down the best abortion I ever had in my whole fucking life. You’re amazing.”

The doctor gave me a look that I interpreted to mean, “Crazy ladies are all the same.” She left. I didn’t care. I loved her.

My companion walked with me to the recovery room, where I did not need to recover, really. There were four or five women in there, with blankets over their legs, eating little packages of Lorna Doones and saltines and drinking juice boxes. I ate some cookies because I was just so happy.

When the escort took me out to my car, I didn’t even look at the protesters, though I did think about what idiots they were for standing there the whole day when I was going home. The local classic-rock station was playing the last minute of the Van Halen song “Runnin’ With the Devil,” and I went to a record store and bought the first Van Halen album on CD and listened to it the whole way home. I’m not a failure, I thought, I have a pretty good car stereo, and I’m not pregnant, and I am not having cramps, and there is no blood in my underwear, not a speck. I felt like the most successful, luckiest person alive. “I live my life like there’s no tomorrow,” David Lee Roth sang, and I was like, “Dude, me too!”

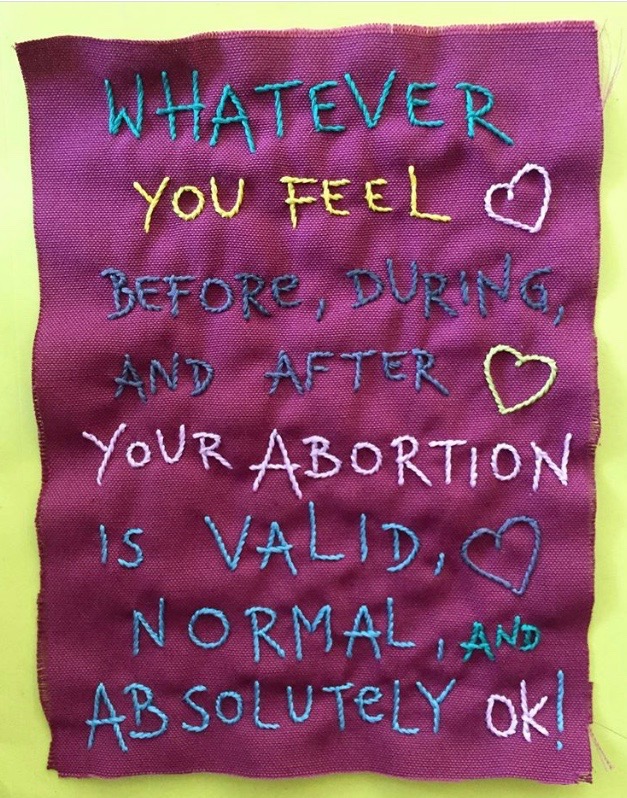

Back at home I made a fire in the woodstove, and for once, it started right away. I went for a run. I thought about all the people — not the pro-life ones, because why bother — but about the pro-choice people and their constant refrains of “no one is pro-abortion. Abortion is always a difficult decision. Abortion is traumatic; it’s so hard. Women struggle so hard with this decision” — and I thought about my mother, shifting the Volkswagen from first to second, telling me in her offhand manner what an abortion was, in the same tone she’d told me why New Hampshire was the Granite State, or what was in a snickerdoodle.